Justice Comes After the War? War Related Sexual Violence and Legal Nationalism in Four Countries of Former Yugoslavia

Although almost two decades have passed, there is still no exact explanation of the causes of the Yugoslav wars, the real scope of their effects, or the actors involved. For the sake of brevity, we will not delve into the reasons that contributed to the disintegration of the Socialist Federative Republic of Yugoslavia. Suffice to say that the Yugoslav wars refer to a series of violent conflicts, precipitated by intense ethnic tensions. The conflicts were separate but related: a short outbreak of war in Slovenia, the Independence War in Croatia, the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and the war in Kosovo and Serbia. The Yugoslav wars resulted in the formation of several sovereign (or prospectively sovereign) nation-states. The Yugoslav wars, especially in Bosnia, Kosovo and Croatia, were to a large extent wars against civilians, subjected to violent and abusive practices on the basis of their ethnicity. Ethnic cleansing was used as a premeditated and calculated strategy to crush the ‘enemy ethnic group’. According to the report of Human Rights Watch, rape was one of the tools of ethnic cleansing “meant to terrorize, torture and demean women and their families and compel them to flee the area” (1995, 8).

In this short paper, we focus on one aspect of transitional justice which was devised to promote gender justice specifically and address the persistent problem of sexual and gender based violence. We consider the implementation of the UN Security Council Resolution 1325, with a special emphasis on point 11 which calls for prosecuting “those responsible for genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes including those relating to sexual and other violence against women and girls”, stressing “the need to exclude these crimes, where feasible, from amnesty provisions” (United Nations Security Council 2000, 3). This particular point is of crucial importance because it obligates all States to pass laws to prosecute crimes of sexual and gender based violence, to bring justice to survivors and their families, to put an end to impunity and uphold the rule of law.

Let us give some general information on sexual and gender-based violence during the wars in the former Yugoslavia. There are many estimates on how many women had to endure the most dehumanizing acts of sexual and gender based violence. Based on reports of various commissions, women’s testimonies, information provided by women’s groups and refugee women, the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women reported in its concluding comments that 25 000 women suffered from the most reprehensible forms of human degradation in Bosnia and Herzegovina alone (see, for example, Skjelsboek, in Skjelsboek, Smith 2001; Olsson & Tryggestad 2001, 77; Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women 1994, 1). The numbers are vague and inconclusive for other countries, but it is certain that rape and other demeaning acts of sexual and gender based violence were purposefully employed as a means of ethnic cleansing.

The UN Commission of Experts reported that in the camps of all three sides – Serbian, Croatian and Bosnian – grave breaches of the Geneva Convention and other violations of international humanitarian law, including killing, torture, and rape, took place. It is stated that the age of women kept in detention camps varied from 5 to 81, while the majority of victims were less than 35 years old. According to the report, the majority of perpetrators were military men, soldiers, policemen, representatives of paramilitary and Special Forces, while most of the cases occurred in settings where the victims were held in custody (United Nations Security Council 1994, 59-60). The rapes were therefore not isolated acts, but deliberate and organized crimes against populations, tools for terrorization, extortion of money from people and families, as well as means for their profound humiliation. The bodies of ‘wrong’ women, the female representatives of adversary ethnic groups, were the main target of these dehumanizing acts.

It should come as no surprise that the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), the official post-Yugoslav mechanism of transitional justice, was the first international criminal tribunal that pronounced convictions for rape as a form of torture, and for sexual enslavement as a crime against humanity. It is also the first international tribunal based in Europe to pass convictions for rape as a crime against humanity (Prosecutor v. Kunarac et. al.). According to the thematic report of the Human Rights Commissioner of the Council of Europe (2012, 24), in 2001 48% of all cases processed before ICTY had elements of sexual and gender based violence. This confirms its widespread use during the Yugoslav wars.

Resolution 1325 had been envisioned as a promising provision for female survivors of war violence and was advocated strongly by women’s groups. It was widely believed that such a provision might bring justice and equal treatment to all women who had suffered sexual and gender based violence during the wars, regardless of their ethnicity.

Let us now quickly interject several points on women’s and feminist organizations in the former Yugoslavia. Even though women’s organizations had their history way before the 1990s (Zaharijević, 2015; Zaharijević, 2017), wars for succession left an enduring mark on them. Women’s grassroots and feminist engagement – their goals, vision of future societal prospects and values they actively promoted – during and after the wars had many strong parallels with the stated goals and recommendations of Resolution 1325. It should not, therefore, come as a surprise that after its adoption in 2000, it was women’s grassroots and feminist groups which became the most ardent advocates of the adoption of Resolution 1325 in their respective states.

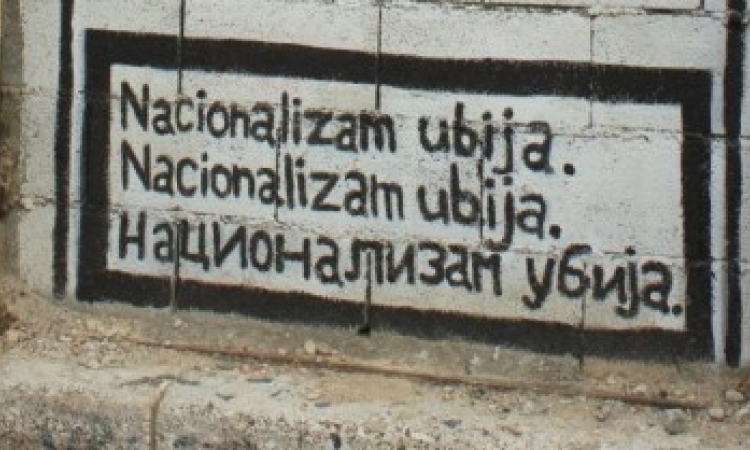

The regulative ideals upheld by women’s grassroots and feminist groups in post-Yugoslav post-conflict societies revolved around politics of peace and human security. They have, however, consistently insisted on the gendered dimension of ‘humanity’. For humanely organised societies to take place, especially after such violent conflicts as were witnessed during the Yugoslav wars of succession, it was believed that justice was to be achieved in an anti-militarist and emphatically antinationalist framework. It was also believed that the Resolution could be used to support activism condemning the war system and militarization.

In our paper we showed in detail that the proclaimed goals promoted by women’s groups – the reconstruction of society in general, with a special emphasis on eradicating sexual and gender based violence, disarmament, and furthering peace and anti-militarist values – remained in the shadow of the gender-mainstreaming aspect of Resolution 1325, limited to inclusion of women in the military and police (Subotić and Zaharijević, 2017). The way Resolution 1325 was implemented decades after the wars were over, testifies to a failure of women’s groups hopes and expectations. The successor states of Yugoslavia have not only failed to implement consistent and collaborative measures in order to provide justice and prevent impunity according to UNSCR 1325 point 11, but they have used those very mechanisms to promote a certain form of legal nationalism.

In defining legal nationalism with regard to sexual and gender violence, we draw on Robert Hayden’s definition of “constitutional nationalism” (Hayden, 1992). Even after the wars were over, nationalism persisted in the laws regulating their most vulnerable effects. With the notion of legal nationalism we wanted to point to the dismal combination of nationalism and the rule of law in the legitimation of the fundamentally nationalist political order decades after the war. Legal nationalism leads to the formation of separate criteria for measuring the humanity and dignity of people who fall inside or outside the sphere of nationally desirable citizens. In other words, our research demonstrates how post-Yugoslav societies nationally abused gendered transitional justice: legal imagery, supposed to transform the lives of victims of sexual violence in war, in fact, turned into the instrument for the re-introduction of nationalism.

We have chosen to analyse four countries: Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Serbia, and Kosovo, as the territories significantly involved in the Yugoslav Wars. By 2014, all of these states had introduced the UNSCR 1325 into their national contexts by adopting action plans for its implementation. The adoption of national strategic documents (NSD) has to be understood as an ambivalent compliance with the largely imposed transitional processes, rather than as the reflection of a strong desire for post-war justice and for the implementation of anti-war and anti-militarist principles feminists fought for during and after the war. The first NSD was adopted in Bosnia and Herzegovina in 2009. Serbia followed suit in 2010. Croatia and Kosovo adopted their NSDs in 2011 and 2014 respectively.

Legal translations of UNSCR 1325 in national documents

The majority of war detention camps where the crimes of sexual and gender based violence took place were located in Bosnia and Herzegovina and it came as no surprise that Bosnia and Herzegovina was the first country to try to implement mechanisms for access to justice for all its women and girls. However, four years after the adoption of the action plan there was still no single reliable database on women victims of rape and other forms of sexual violence. Regardless of the fact that the Bosnia and Herzegovina action plan insisted on providing assistance to all women of Bosnia and Herzegovina who were victims of sexual and gender based violence, all three entities still do not have synchronized legislation for sexual and gender based violence. This is very much due to the fact that legislation on rape and the definition of a civilian victim of war has been differently regulated under domestic criminal legislation in Bosnia and Herzegovina. For our purposes here, suffice to say that the full legal translation of 1325 is severely handicapped by the Bosnian political and legal system, i.e. by its internal constitutional division of jurisdiction between its constitutive entities. This fundamental division is further inscribed in other legal measures, such as those defining categories of survivors of war-related sexual and gender based violence, the percentage of bodily injury, and citizenship, which provide opportunities for the emergence of legal nationalism.

In Serbia, where both the post-conflict character of the state and its involvement in the war have been denied, the category of survivors of war related sexual and gender based violence is simply non-existent. The actors, most prominently feminist anti-nationalist and anti-militarist groups, who have persistently encountered this denial – and with it, the hidden Serbian nationalism visible in the reluctance of the Serbian state to face its past – were blatantly excluded from negotiations. Serbia was thus, on the one hand, the only of the four countries under analysis where no representative of women’s groups took part in the process. Gender justice has been almost entirely reduced to equalizing the number of men and women in arms. The national action plan does not mention prosecution of the cases of sexual violence committed by the Serbian military, police and paramilitary units on its own territory, the territory of Kosovo or other territories of the former republics of the SFRY. In other words, in terms of post-conflict gender justice, Serbia has not implemented a single activity in relation to the improvement of the lives of women survivors of war-related violence, i.e. women refugees from countries of former Yugoslavia, internally displaced women from Kosovo and women who suffered sexual and gender based violence.

In Croatia and Kosovo alike, due to the nature of the wars which took place on their respective territories (the “Independence war” in Croatia, and the “Liberation war” in Kosovo), UNSCR 1325 found their fullest applications. Unlike Bosnia and Herzegovina where the politico-legal administration delays justice, or Serbia where there is a reticent denial of injustice, Croatia, and Kosovo fully recognize that there were gross instances of injustice towards women and show readiness and capability to offer certain redress. However, by bending certain legal definitions – of the categories of sexual and gender based violence, of the nature of the war or by defining specific time frames – both Croatia and Kosovo introduced legal nationalism in their translation of UNSRC 1325.

Conclusion

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights ends with a claim that everyone – every woman and man – is entitled to a social and international order in which the rights and freedoms set forth can be fully realized. Everyone, in other words, has the right to peace. Resolution 1325 may be seen as the result of the theory and practice of the transnational feminist movement, an effect of a long struggle to affirm equal rights of women to define how social and international order should be structured. Women’s grassroots and feminist groups in post-Yugoslav countries believed that Resolution 1325 could be used to promote a more just, more equitable future for societies that endured severe conflicts. This assumed bringing justice to those who were treated unjustly and producing societies in which past injustices would not be repeated in the future.

But did that happen? The direct result of the adoption of national action plans is the gradual increase in the number of women in armies and police forces, and the progressive gendering of the security sector. The process of securitization, very much relying on the principle “ add women and stir”, does not substantially address post-conflict reconstruction or the reintegration of its survivors.

We wanted to show that the adoption of national strategic documents, prompted by concerns for reconstruction and reintegration, produced new exclusionary politics which in fact goes against both reconstruction and reintegration. Women’s grassroots and feminist organizations hoped that Resolution 1325 could provide justice to all women survivors. However, the implementation of Resolution 1325 got trapped and side-lined by the state, political parties, nationalists, and different ethnic and religious groups. Instead of being documents that offer post-war justice to all women survivors of sexual and gender based violence, national strategic documents are strengthening dominant ethnonational victimhood through legal nationalist excluding narratives.

Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women. 1994. Concluding Comments of the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women: Bosnia and Herzegovina, Thirteenth Session 17 January–4 February 1994, Excerpted from: Supplement No. 38 (A/49/38). Retrieved from http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/cedaw/cedaw25years/content/english/CONCLUDING_COMMENTS/Bosnia_and_Herzegovina/Bosnia_and_Herzegovina-Special_report.pdf

Council of Europe. 2012. Posleratna pravda i trajni mir u bivšoj Jugoslaviji: Tematski izveštaj komesara Saveta Evrope za ljudska prava. Retrieved from Council of Europe website https://www.coe.int/t/commissioner/source/prems/Prems45112_SER_1700_PostwarJustice.pdf

Hayden, M. R. 1992. “Constitutional Nationalism in the Formerly Yugoslav Republics.” Slavic Review, 51(4): 654–673.

Olsson, L. & Tryggestad, L. T., eds. 2001. Women and International Peacekeeping. London and Portland: Frank Cass.

Prosecutor v. Kunarac et.al. (Case No. IT-96-23 & 23/1. Judgment passed 22 February 2001).

Skjelsboek, I. and Smith, D., eds. 2001. Gender, Peace, and Conflict. London: Sage Publications Inc.

The Human Rights Watch. 1995. Global Report on Women’s Human Rights. New York and Washington: Human Rights Watch.

United Nations Security Council. 1994. Letter dated 24 May 1994 from the Secretary-General to the President of the Security Council (S/1994/674). Retrieved from United Nations International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia website: http://www.icty.org/x/file/About/OTP/un_commission_of_experts_report1994_en.pdf

United Nations Security Council. 2000. Resolution 1325 (S/RES/1325). Retrieved from United Nations website: http://www.un.org/womenwatch/osagi/pdf/res1325.pdf

Zaharijević, Adriana. 2015. “Dissidents, disloyal citizens and partisans of emancipation: Feminist citizenship in Yugoslavia and post-Yugoslav spaces.” Women’s Studies International Forum 49: 93–100.

Zaharijević, Adriana. 2017. “The Strange Case of Yugoslav Feminism: Feminism and Socialism in 'the East'.” The Cultural Life of Capitalism in Yugoslavia: (Post)Socialism and Its Other, eds. Jelača D., M. Kolanović and D. Lugarić, 263-283. London and New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

This paper was presented at the 6th International Gender Workshop, organized by the Heinrich Boell Foundation in Lviv in March 2017. The paper is a short version of the text “Women between war Scylla and nationalist Charybdis: Legal interpretations of sexual violence in the countries of former Yugoslavi ”, published in: Lahai , John and Moyo, Khanyisela, eds. Gender in Human Rights and Transitional Justice, Springer International Publishing, 2017.

Join the Discussion!